Select Writing

“Less Than Perfect,” Boston Globe Magazine

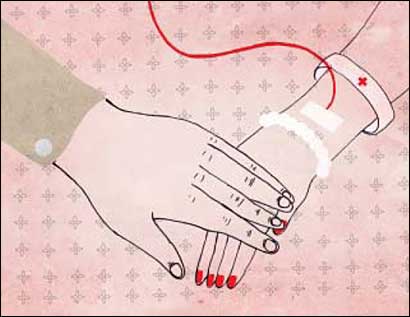

Less Than Perfect

A young woman discovers that revealing a secret can be more powerful than making a “good” impression.

(Illustration / Christopher Silas Neal) |

By Laurie Edwards | January 8, 2006

I met John at the coat check of a downtown bar where I was hosting a New Year’s Eve party. We chatted briefly, just long enough for him to notice my smile and for me to notice his startling blue eyes. Hours later, we found each other again, just in time for the midnight kiss. Sound too good to be true? Of course. It all happened, but the real story is always more complicated.

I had spent the afternoon debating whether I should even attend my own party. I had been released from the hospital just two days earlier and was completely exhausted. As unwelcome accessories to my black cocktail dress and long hair pulled up, my arms were trailed with deep purple bruises, remnants of collapsed veins from IV insertions. I have bronchiectasis, a chronic condition, meaning bacteria and mucus collect in my lungs, causing infections, decreased oxygenation, and frequent hospitalizations. I’d just spent Christmas in the hospital, as well as Thanksgiving and several weeks of September and October. I was more interested in recovery than romance.

“What happened to your arms?” John asked as we moved from the edge of the crowded dance floor. I pulled at my wrap, which had slipped down around my elbows.

Emboldened by champagne and weary of the charade I had carried on all night—all my life, really, in situations like this—I did something I’d never done before with a cute, friendly guy I might actually want to see again: I told the truth. And instead of discreetly excusing himself as I expected, John asked for my phone number. Instead of the total regret that I expected, I felt a tiny twinge of relief.

Like most 20-somethings, I wanted to be vibrant and appealing, not weak and sickly. The pills, tests, surgeries, and daily sessions of physical therapy that make up my life are not exactly dating-friendly. What guy wants to hear about medicines and mucus over martinis?

My friends and family knew all about it. They visited me in the hospital, brought me tea and trashy magazines, and watched hospital cable with me. But in the dating world, first impressions in bars often mean only impressions, and chronic illness didn’t fit easily into that scene. So I cultivated the art of casual conversation, perfected the ability to deflect personal questions, and avoided the very topic I felt defined me.

In the back of my mind were the words said a few years earlier by a man I had cared about: “Thinking of your life stresses me out. I can’t do this.” Careless words, but they resonated. I didn’t think someone new would ever want to get involved with me when there were plenty of healthy people around. I gave John my number doubting he would call.

But he did call, and within a couple of weeks, we had already bypassed the need for what my friends call the “RDT”—relationship-defining talk. Given our obvious feelings for each other, the idea of affirming our exclusivity was ludicrous.

As a new couple, we survived our first dinner with my parents, our first real fight, and our first “I love you.” But soon into it, we also experienced our first surgery together, our first emergency room crisis, and a slew of messy infections.

I waited for the reality of it all to overwhelm him, for my illness to crowd him right out of our relationship. I told myself I would understand if it did.

“None of this is ever going away, John. Wouldn’t you rather be with someone healthy?” I asked one cold winter day. I spoke with the halting confidence of someone who knew the answer but needed to hear it anyway.

“No, because then it wouldn’t be you,” he said without hesitation.

And with that, I started to get over myself. A quirky habit, a misshapen body part, a childish and irrational fear—we all have something we want to keep hidden, something we fear will diminish us in another’s eyes. It wasn’t John’s perception of my illness that threatened to hold our relationship back; it was my own.![]()

Leaps of Faith

When you’re about to get married, a divorce in the family really shakes things up.

(Illustration / Christopher Silas Neal) |

By Laurie Edwards | April 9, 2006

The day my fiance, John, and I were scheduled to pick out our wedding invitations, we spent the morning helping my brother move out of his house. He had just announced his divorce, and by the time we loaded the first suitcase, we knew switching gears from packing up the remnants of a family to debating font sizes and ribbon width would be impossible.

We drove home instead of going to our appointment. I cried; John stared straight ahead. As we neared my street, we started to argue over whose method of grieving was more appropriate: Mine was too emotional, his too rational.

Once the fighting began, it lasted for several weeks. We fought about little things like radio stations and movies and big things like money and kids. We even fought about fighting: who started it, whose tone was more condescending. To outsiders, we tried hard to be the same smiling couple we’d always been, but in private we hardly recognized ourselves. The irony of that point wouldn’t hit me for weeks.

We were upset about the divorce, of course, not the radio, and we were arguing out of fear, not anger. Every now and then, we’d stop and reassure each other by saying, “Never us.” But deep down lingered the question: No one gets married thinking they’ll wind up divorced. What makes us different?

John and I had said “I love you” within a few weeks of meeting. On a hazy August night just seven months later, he proposed. As if by magic, as he stood up to place the ring on my finger, the band began to play our song, “Our Love Is Here to Stay.” John swore he hadn’t planned it. We were convinced we were meant to be.

Intellectually, I knew the statistics were not promising, but emotionally they had little impact on me, since divorce had always been something that happened to other people. Suddenly, we couldn’t hide behind an abstraction anymore, and my brother’s divorce was so real it threatened to destroy our relationship. The thing is, marriage is never really just about two people. When we say “I do,” we bring all the people who matter most into the union with us.

It’s convenient to look back and say we had some inkling of their divorce, but we really didn’t see it coming. No one did. In fact, we’d just asked my brother and his wife to be in our wedding. I had grown up watching them, and they were the kind of couple I had hoped John and I would be.

Like all couples marrying in the Catholic Church, John and I had completed a marriage prep course where we earnestly tackled issues like finances, child rearing, spirituality, and sexuality. We were confident in our compatibility, but until confronted with the divorce, we hadn’t thought about what would happen if we strayed from those points of agreement. Because of my brother, we were forced to have some tough conversations that would have been easy to avoid otherwise. We hated that our lesson was at the expense of our family’s pain, but we left that phase of our relationship with more strength and less naivete than we had before it.

Joining your life to someone else’s is the biggest risk there is. So why do it, especially given the bad odds? The only guarantee you can have is the knowledge that you love someone. That’s what John and I had when we ultimately married; that’s what my brother and his wife had had; that’s all anyone really has. I have to believe that that knowledge alone is worth the risk. There will always be the chance for failure, but there will always be the chance for success.

As newlyweds, when we think about our future, we think of it in terms of how each of us will grow without our growing apart. Love deepens; it bends and changes to be what we need most, even if we don’t always see that right away. It will grow with John and me if we give it the chance, and that’s all we need to know.

Laurie Edwards is a writer based in Boston. E-mail comments to coupling@globe.com.![]()